When the soul has suffered all it can.

—“There is a Languor of the Life,” Emily Dickinson

Holy tylium ship, Batman! The wheels on the bus keep popping off one by one, don’t they? And where last week’s episode was filled with ever more painful revelations and monumental open-ended questions, this week we pause for a breath, zooming in on the personal fallout and pressing at the wounds in search of a little relief. And still the hits keep coming, like the surprises, and the pain is no less great.

“Oh, Felix, what are you doing?” Baltar asked at his trial, such a long time ago, when Gaeta told a lie to try to right a wrong. Gaeta, whose natural inclination to expose a lie was the reason Baltar had been made president in the first place. Whose allegiance has been questioned and tested over and over again, and whose desire to do the right thing, always, is now driving him to choose another side. And who knows? Maybe it is the right thing to do. Who looks more sane at this point: Roslin or Zarek? Would you still trust Roslin and Adama? When the one has all but disappeared and the other seems determined to take you down an almost unfathomable path? Would you believe that they have any clue where to go from here, when every direction they’ve guided you in so far—the exact route you then plotted yourself—has ended nowhere? I don’t think so. I think you might feel cheated, too, that you might realize you’d been forced into the service of another lie, and placed a bet on a losing hand (and been handed your own leg as a thank you for your trouble). And I think you might then allow yourself to help chart a new course, for a new leader, in the hopes of finding a new way and righting a different set of wrongs.

And the thing about Tom Zarek is that he has always made sense, in his own shifty fashion. His instincts, coupled with his great capacity for self-preservation, that shark-like ability to sniff the waters for blood and then swim unerringly in the right direction, have always been grounded in reason, not prophecy. He’s of the people in a way that Laura Roslin, for all her absolute devotion, has never been (though his commitment is also a choice in a way that hers never was). But his ear is tuned differently to the fleet’s needs and he hears them as individuals; unlike Laura, he also listens to what they’re saying. Likewise, he has never fancied himself their savior; he can deliver a speech to the Quorum in a voice that they recognize, instinctively, as one of their own, and not that of a priestess delivering orders from on high, or even a schoolteacher bidding them to be quiet. And the mayhem that will surely follow is a price he’s willing to pay to forge a future that’s free of the broken promises and good intentions that have ended up leading them to nowhere.

Then, alas, poor Tyrol! How could we have guessed that he still had more to lose? Our natural born negotiator, the decent, plodding, blue collar man in the middle—who starts out trying to cement the alliance between the fleet and what we’ll refer to, optimistically, as the Good Cylons—appears at the end to be sliding down another slope entirely when he learns that the last thing tethering him to humanity is in reality not his at all. And to think that this little out-of-left-field bombshell (driven as it was by a writers’ necessity and through a sloppy series of declarations) would lead us straight down a wormhole to good ol’ Hot Dog, of all people! Weird, silly, unexpected, beautiful. Ditto the scene in which Tyrol instructs Hot Dog on how to care for a child that up to now he has believed to be his own and likely, in some ways, always will. (Sidenote: I won’t follow the tack that this whole Hot Dog indiscretion casts Cally in a negative light, or that it makes her character even more of a whipping boy for the writers, or whatever the female version of “whipping boy” might be that doesn’t make it sound even more pornographic; instead, I think it makes her more human. The one thing Cally never possessed was a barometer for her own best interests.)

And then, at last, we have our lovers. (Let’s stop here for a second and appreciate…I don’t know, just the ground of that sentence. The fact that it has finally, irrevocably, indisputably come to be, after everything that’s passed.)

Sorry. Moving on: Laura Roslin is still, obviously, off her nut. Or is she? Again, doesn’t this path make perfect sense for her to follow, or at least contemplate? You can see it in her face, in the way that she carries herself and lifts her head again, finally meets Adama’s eyes, even in the frankly awkward sight of her physically casting aside her presidential and prophetic mantle and strapping on a pair of running shoes: she is free. Has set herself free, in fact, has finally made a decision in favor of her own fate rather than swallowing what has been prescribed as her destiny. Regardless of how short and painful that future might be, at least she can say she has chosen the pain, and the method by which it’s delivered. For if there’s anything Laura Roslin still knows to be true, it’s the fact that she’s going to die. Of course it’s also possible that next week she’ll be digging frantically through Galactica’s trash bins in search of those discarded meds, so who knows? Love can do funny things to people. And I fully expect she’ll be slipping back into that executive chair before too long, anyway, because no matter how much she may want and have actually earned her freedom, she is also not a quitter. Or a deserter. Or whatever.

Plus she has her live-in boyfriend to worry about now, and how much did I love this episode’s Caretaker Admiral, grasper of straws and impossible things, brusher of teeth, collector of inevitable trash? Very much, thank you. Going nose-to-nose with Zarek always brings out the best of his fire and brimstone, and when he’s cracking down hard in defense of what’s left of his authority and backing it up with equal parts threat, action, and presumption, so much the better. And he does it all without the luxury of getting to choose; his is not a burden he can afford to lay down, and he knows it. He pulls himself out of bed every morning surrounded by and almost literally buried in his duty, and this is not a man who rests in the first place. This is a man who has reached his breaking point and still manages to go through the motions, who has no idea where to turn next, or which lie is safe to tell in order to keep them all moving together toward this imaginary new somewhere. Of course he hates his job, and yet he does it. Force the whole fleet to be BFFs with the Good Cylons? Why not? It just might work. And if he reaches for the bottle a little more often these days, and mixes that booze with pills that he picked up god knows where to alleviate god knows what, how can he be blamed for that? For frak’s sake, the old man is tired!

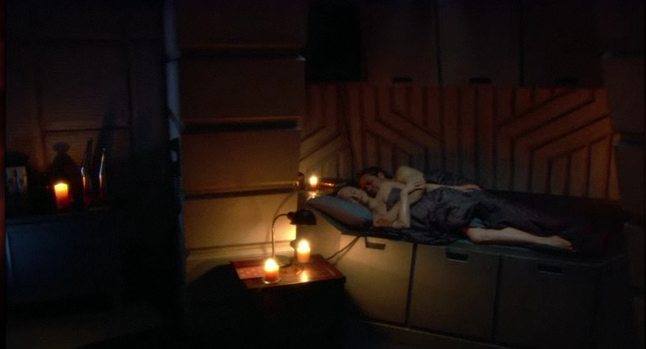

Who can blame either of them for being tired? For wanting to let go of it all—the responsibility and the guilt—and then actually doing so, for a few short hours here, at the end of the world? To see these two people, these last leaders of humanity who have become each other’s counsel and conscience, finally at peace, finally able to lie in each other’s arms—smiling! laughing! happy!—for a rest that is both well deserved and years in the making, how can they be blamed for that? I’m sure the world will go back to hell in the morning, and everything will be wrong once more.